The most notorious immigration legislation in American history was enacted by the U.S. Congress one hundred years ago. The Immigration Act of 1924, which President Calvin Coolidge signed, significantly reduced immigration from eastern and southern Europe and virtually barred it from Asia.

Nevertheless, the law implemented this in a somewhat subtle manner: it established a quota. In 1890, lawmakers determined the number of immigrants from each European nation who were domiciled in the United States. Subsequently, they retained 2% of this total. Each year, only that number of newcomers from a specific country could be admitted. Before the end of the 19th century, the number of immigrants from outside western and northern Europe was still relatively small, meaning their 2% quotas would be minuscule.

In summary, the Immigration Act was blatantly discriminatory, with the intention of reversing the demographic trend. One of its sponsors, U.S. Rep. Albert Johnson, warned the House Committee on Immigration that “a stream of alien blood” was poisoning the nation.

Torn between “the American dream” and fears of an ungovernable “melting pot,” Americans have always viewed immigrants ambivalently. In 1924, as is true today, many citizens thought in terms of “good” immigration versus “bad” immigration. Between the two, 1890 was a dividing line in their imaginations.

As a historian of immigration and religion, I’m astounded by three shifts in American attitudes toward immigration over the course of the 19th century.

Far more than ethnicity, religion

Eugenicists were preoccupied with the issue of race by the 20th century. In contrast, early 19th-century nativists worried more about religion and how to protect America’s culturally Protestant foundations from Catholic immigrants, most of whom, at this point, came from Ireland and Germany. A long-standing paranoia was the source of this anxiety: Could foreigners who professed allegiance to an infallible pontiff become loyal citizens of a republic?

Rev. Lyman Beecher, a Cincinnati minister, suggested that this may be the case—but only after exerting significant effort on their behalf.

“What is to be done,” he asked in his influential 1835 tract “A Plea For the West,” “to educate the millions that, in twenty years, Europe will pour out upon us?”

Many nativists of this time shared similar fears of immigration, declaring that the Catholic Church was orchestrating “a foreign conspiracy” against the liberties of the U.S., aimed at stripping away constitutional freedoms and rigging elections on behalf of Vatican interests.

For Beecher, the development of “intelligent, virtuous, and industrious emigrants” necessitated the integration of public education and Protestant influence. He hypothesized that by employing this method, Catholic populations could be transformed into patriotic Americans, who may eventually adopt Protestant congregations. This type of mentality was prevalent.

Local, as opposed to federal

The virtual absence of significant national immigration legislation was a second distinct contrast between earlier nativism and its later 19th-century counterpart. Nativists in the early American republic prioritized assimilation over exclusion, despite their apprehensions regarding foreign Catholic influence. They saw immigration as a cultural, religious and educational concern more than an arena for federal policy.

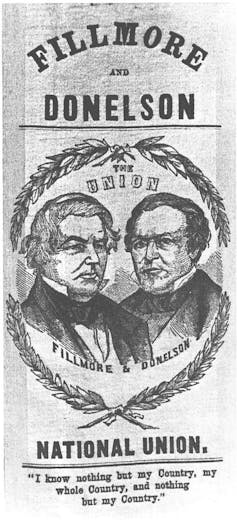

The anti-immigrant American Party, or Know-Nothing ticket, did flourish in the 1850s before imploding over the issue of slavery. The Know-Nothings made significant gains in state and municipal elections, winning mayoral elections in cities such as Boston and Philadelphia.

In Beecher’s hometown of Cincinnati, however, the nativist ticket failed to dislodge the incumbent Democratic mayor. The Know-Nothing’s reliance on Protestant German support against the immigrant Catholic vote exposed the frailty of coalition politics and the subjective nature of distinctions between “good” and “bad” immigrants there and elsewhere. Likewise, the one major immigration proposal of the American Party—a required 21-year waiting period for new immigrants seeking citizenship—never got past the drawing board.

Although overseas immigration declined in the mid-1850s, Know-Nothing activism did not necessarily explain this downturn. Instead, declining immigration reflected economic cycles, such as the end of Ireland’s peak famine years.

The conclusion of an era

Westward expansion was the ultimate variable that influenced public sentiment regarding immigration. The majority of Americans saw the frontier as a pressure relief valve for their rapidly expanding country, providing opportunities and land to ambitious settlers. But by the late 19th century, the era of Manifest Destiny—the belief that the country’s destiny was to spread from sea to sea—was nearing the end of its road.

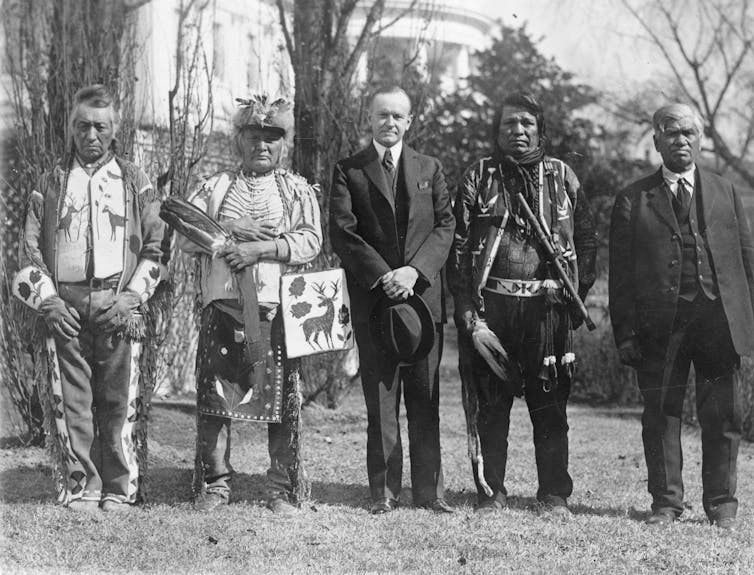

After signing the Indian Citizenship Act, President Calvin Coolidge stands outside the White House with four Osage leaders.

Revealingly, the 68th U.S. Congress, which passed the Immigration Act of 1924, also passed the Indian Citizenship Act the following month. While simultaneously confirming that all Native Americans were U.S. citizens at birth, the law also emphasized their reliance on reservation lands as tenants of the federal government.

The frontier’s closure not only represented a turning point in the history of immigration but also a significant shift in the relationship between the United States and its Indigenous peoples. The government integrated Native Americans into the fabric of society yet withheld the full benefits of citizenship, including guaranteed voting rights.

New era, new prejudice

By the late 1800s, the children of 19th-century immigrants—mostly northern Europeans—had largely assimilated into American society, despite the anti-German prejudice that was common during World War I.

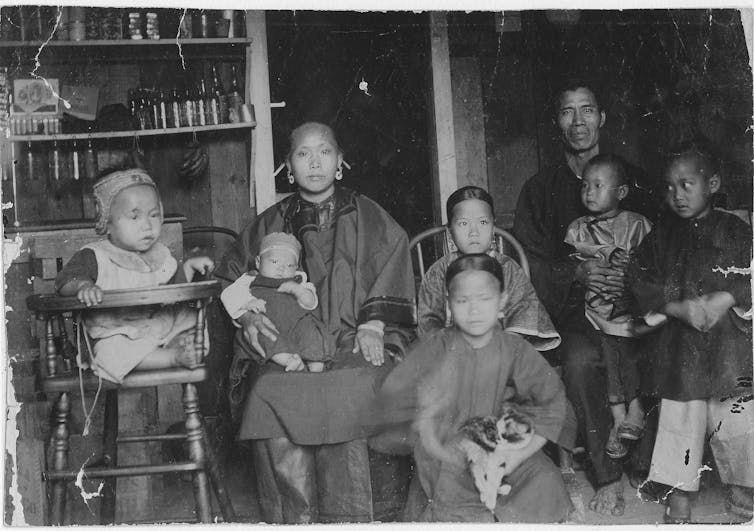

In the interim, the number of new immigrants from other parts of Europe and beyond was increasing, and they were also subjected to discrimination. Specifically, East Asian immigrants were subjected to suspicion. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 set a moratorium on all immigration from China, alleging that Chinese immigrants endangered “the good order of certain localities.”

Generally speaking, racial rather than religious prejudice dominated anti-immigrant politics by the late 19th century, although these boundaries blurred in the case of antisemitism against Jewish immigrants from eastern and central Europe. The popularity of “racial Darwinism” was at its height: pseudoscientific thinking that misconstrued Charles Darwin’s ideas about evolution, applying ideas such as “survival of fittest” to human society. A sizable number of Americans with northern European ancestry accepted the ensuing dogma of “Nordic” superiority.

The racism behind the 1924 Immigration Act even prompted a reference in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” the celebrated novel published the following year.

“Have you read ‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard?” inquires Gatsby’s antagonist, Tom Buchanan. This thinly veiled reference alludes to “The Passing of the White Race,” a 1916 manifesto by avowed white supremacist Madison Grant, which was approvingly cited in the congressional debates of 1924.

The historical timeline since

The quota system was not repealed until 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, praising “those who can contribute most to this country—to its growth, to its strength, to its spirit.”

Ever since, U.S. immigration has avoided overt discrimination by national origins, with one exception: Donald Trump’s 2017 executive order temporarily barring entry visas from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

Nevertheless, the Immigration Act of 1924 continues to serve as a historical benchmark, representing the enduring conflicts between ethnic exclusivity and civic inclusion in American society.